Previously on Let’s Build a Regex Engine, we learned about formal grammars and defined one for regex, parsed the pattern, and compiled it to Nondeterministic Finite Automaton (NFA) There is now only one thing left to do – use NFA to find matches in the input strings.

Matcher is still a work in progress. I’m sure I got at least some of it wrong. I’m confident in the parser and the compiler, but there doesn’t seem to be a single best matching algorithm – they all seem to address different problems in different ways. In this post, I explore two algorithms that are, to the very least, simple and clear from the CS standpoint. They are not necessarily going to be the best in practice.

Matching #

What do we mean when we say “match”?

A conventional regex engine can find the first match in the string. It searches the entire input string for the first occurrence of the regular expression.

let regex = try Regex(#"<\/?[\w\s]*>|<.+[\W]>"#) // Finds tags

regex.firstMatch(in: "<h1>Title</h1>") // Returns "<h1>"

Check if the string matches the given regex1. It can potentially be simply implemented as firstMatch(in: string) != nil.

regex.isMatch("<h1>Title</h1>") // Returns true – found at least one tag

Find all matches in the string:

for match in regex.matches(in: "<h1>Title</h1>\n<p>Text</p>") {

print(match.value)

// Prints ["<h1>", "</h1>", "<p>", "</p>"]

}

Return all groups which were captured along the way, if there are any:

let pattern = #"(\w+)\s+(car)"#

let string = "green car red car blue car"

let matches = regex.matches(in: string)

// Finds matches: [

// Match(fullMatch: "green car", groups: ["green", "car"]),

// Match(fullMatch: "red car", groups: ["red", "car"]),

// Match(fullMatch: "blue car", groups: ["blue", "car"])

// ]

It also needs to be able to do all of these things efficiently, potentially on large inputs. This is a tall order!

We can start by finding the first match in the string. If we build this, the rest of the features will be relatively easy to implement. But first, we need to understand what it means to execute an NFA.

Algorithms #

There are many algorithms for generating state machines for regex, and for performing the actual matches. Each has its own performance characteristics and feature set.

Some algorithms use DFA, which, as I mentioned in the previous article, is not covered by this series – few modern engines use it. Most use NFA.

I implemented two different matching algorithms for NFA.

The first one uses backtracking. It offers some powerful features, like backreferences, at the expense of potentially exponential time complexity. Similar algorithm can be found in .NET and other platforms.

The second one guarantees linear time complexity to the length of the input string. It is useful when you want to be able to handle regular expression from untrusted users.

You can find many different names and descriptions of both of these algorithms. I will present them from a slightly different angle, taking some ideas from graph algorithms. I find this approach more compelling and hope it doesn’t add to confusion.

Graphs #

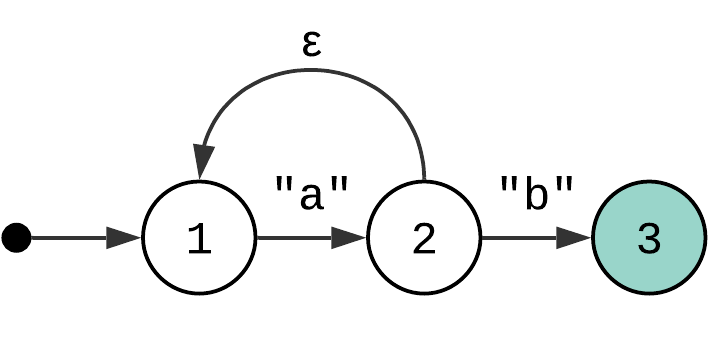

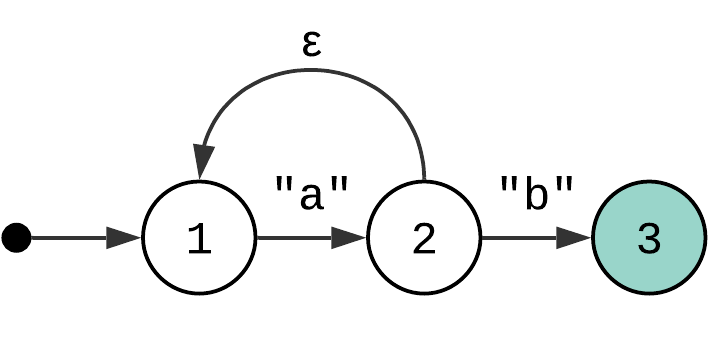

Let’s revisit an NFA from the previous article:

Does it remind you of something? There are nodes – states. There are edges which connect nodes – transitions. Yes, it is a directed graph (or digraph). Which means that any algorithm that can be performed on a graph can also be performed on this state machine! Or does it?

The state machines can be interpreted as a directed graph, but they are not limited to them. One of the extensions is that each edge (or transitions) has associated conditions. The conditions depend on the current state – the position in the input string. Which means that to navigate the graph, you also need to keep track of the state. But the main take away is that you can navigate it to reach the accepting state. Speaking about the accepting state.

Pathfinding #

The accepting state is the one that we are trying to reach. And it means that we have a pathfinding problem on our hands.

When it comes to pathfinding (and many other graph algorithms), there are two ways of approaching it: depth-first search (DFS) and breadth-first search (BFS). Let’s start with the former and see how it goes.

DFS (Backtracking) #

The idea of depth-first search (DFS) is that you start at the root node and explore as far as possible and backtrack if the search fails. “As far as possible” in general means always taking the very first edge leading from the node and ignoring the remaining edges until the path proves to be a dead end and you have to backtrack.

DFS would normally keep track of the already encountered nodes. This works when there is no reason to revisit the same node twice. In our case, there is. The reason is the input string and the conditions. The search from the same node might lead to different results depending on the input string. So we don’t keep track of the encountered nodes, but we need to make sure that every time we perform a transition it consumes a portion of the input. This is how we guarantee that the algorithm finishes2.

Let’s take the NFA from the example above and the input string “aaab”.

If you were to use DFS search, you would end performing the following steps:

State Input Transition (State)

---------------------------------------

1. 1 "aaab" Consume "a"

2. 2 "aab" Epsilon

3. 1 "aab" Consume "a"

4. 2 "ab" Epsilon

5. 1 "ab" Consume "a"

6. 2 "b" Epsilon

7. 1 "b" No match, backtrack to state 2

8. 2 "b" Consume "b", match found

Implementing DFS #

This is a simplified implementation of DFS search:

func firstMatch(in string: String) -> Substring? {

// Perform search starting from every possible index in the input string

for index in string.indices {

if let endIndex = endIndexOfFirstMatch(in: string[index...], index: index, fsm: <#compiled_regex#>, state: fsm.initialState)) {

return string[index..<endIndex]

}

}

return nil

}

func endIndexOfFirstMatch(in string: Substring, index: String.Index, fsm: FSM, state: State) -> String.Index? {

guard !fsm.isAcceptingState(state) else {

return index // Found a match!

}

guard index < string.endIndex else {

return nil // The string is empty, nothing we can do

}

for transition in fsm.transitions(from: state) {

guard transition.isTransitionPossible(string, index) else {

continue // Reached a dead-end

}

let nextIndex = string.index(index, offsetBy: transition.isEpsilon ? 0 : 1)

if let endIndex = endIndexOfFirstMatch(in: string, index: nextIndex, fsm: fsm, state: transition.endState) {

return endIndex

}

}

return nil

}

This is a classic backtracking pathfinding algorithm. Keep in mind that this is a simplified version. You can find the actual implementation on GitHub.

Lazy vs Greedy Quantifiers #

The algorithm finds the first accepted path, which is not necessary the longest or the shortest one. What does it mean in practice?

Consider the following regex “a*”. If you simulate the backtracking algorithm applied to the input “aa”, it will return “aa”. Why? When you reach the line for transition in fsm.transitions(from: state), the first transition in the list is always going to be the one that consumes “a”, not skips it. This isn’t by chance.

By default, all quantifiers are greedy. The alternative to greedy quantifiers are lazy quantifiers3. With a backtracking algorithm like the one outlined above, implementing lazy quantifiers is relatively easy. All you need to do is reverse the list of transitions so that “skip the character” transition is the first one on the list.

But why do these quantifiers exist? They control the shape of the matches. But they are often used to tune the regex engine performance by limiting backtracking. But what is the problem with backtracking?

Catastrophic Backtracking #

Consider regex "^(a+)+$" with nested quantifiers. If you were to test this regex on regex101.com with an input strings which don’t quite match the regex, it will produce the following output4:

- "aaaaX" – 64 steps, ~0ms

- "aaaaaX" - 128 steps, ~0ms

- "aaaaaaX" – 256 steps, ~0ms

- ...

- "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaX" – 524299 steps, ~231 ms

- "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaX" - catastrophic backtracking

I won’t cover the exact details why it happens, you can read more here if you’d like. If you were to simulate the expansion of the NFA when you navigate it, you will see that the number of possible paths doubles at each step.

Catastrophic backtracking is not the end of the world as many people suggest it is. In general, an NFA engine like this (which include .NET regular expression engine and NSRegularExpression) places the responsibility for crafting efficient, fast regular expressions on the developer5. The problem is when the regexes are not controlled by the developer, and regex can be used for ReDoS attacks.

Is there anything we can do about it? The answer is yes. And this is where the second algorithm comes in.

BFS #

Breadth-first search (BFS) is another search algorithm which, unlike DFS, explores all the neighbor nodes prior to moving to the nodes at the next depth level. Just like with DFS, we won’t simply use the BFS algorithm itself, but we can apply its principles.

The idea behind this new regex matching algorithm is to take an input character and find all states reachable from the current state after consuming a single character. By doing so we might encounter multiple epsilon transitions in the NFA. If we remove all the epsilon transitions, and keep only the ones that consume a character, we essentially re-construct a single DFA state with all the possible transitions.

The idea might seem straightforward but there is a lot nuance. Every engine, that implements this algorithm, does it slightly differently. I’m also currently in the process of implementing it. You can find the latest version on GitHub.

Longest Path #

When an algorithm finds a potential match, it doesn’t stop the search immediately. Instead, it performs an exhaustive search to find the longest match. The requirement to always return the longest match is part of the POSIX regex standard6. It also happens to make sure that all quantifiers have greedy behavior which most users expect.

Comparing Two Algorithms #

Both algorithms are designed to solve the same problem, but they are different in many aspects, including performance and provided features.

DFS can be very fast given when the pattern is well written. In many cases, it can return the result in linear time and faster than the BFS version would. But it doesn’t prevent catastrophic backtracking. It places the responsibility on the developer to come up with the optimal regex pattern.

BFS, on the other hand, is immune to catastrophic backtracking7. One of the engines that uses a similar algorithm is RE2 created by Google. Its goal is to be able to handle regular expressions from untrusted users.

The BFS immunity to catastrophic backtracking comes at a performance cost. It performs an exhaustive search to guarantee that it finds the longest possible match. It also makes certain features like lazy quantification very tricky to implement – I personally didn’t. And it makes implementing certain features like backreferences impossible.

Traditional NFA engines are favored by programmers because they offer greater control over string matching than either DFA or POSIX NFA engines. Although, in the worst case, they can run slowly, you can steer them to find matches in linear or polynomial time by using patterns that reduce ambiguities and limit backtracking. In other words, although NFA engines trade performance for power and flexibility, in most cases they offer good to acceptable performance if a regular expression is well-written and avoids cases in which backtracking degrades performance exponentially.

- Benefits of the NFA engine, Microsoft

Whether these trade-offs are significant or not is up to the developers who use these tools. I can see how for many of the possible usages they aren’t. That’s probably the reason why most of the popular engines, like the ones found in .NET, Foundation, Go, JavaScript, and Python, all use different algorithms.

Optimizations #

String-Searching #

We’ve already established in the previous article that a pattern consisting of multiple characters in a row can be compiled into a state machine with a single transition with a condition “does an input string has the given prefix?” (string.hasPrefix(:)). This allows the matcher to use a faster string searching algorithms which improves the time complexity from O(nm) to O(n+m), where n is the size of the input and m is the size of the pattern.

Regex also performs this optimization. It adds a significant level of complexity to the matcher. I’ve extracted the optimizations into separate code blocks and commented them so that they don’t clutter the core implementation that much.

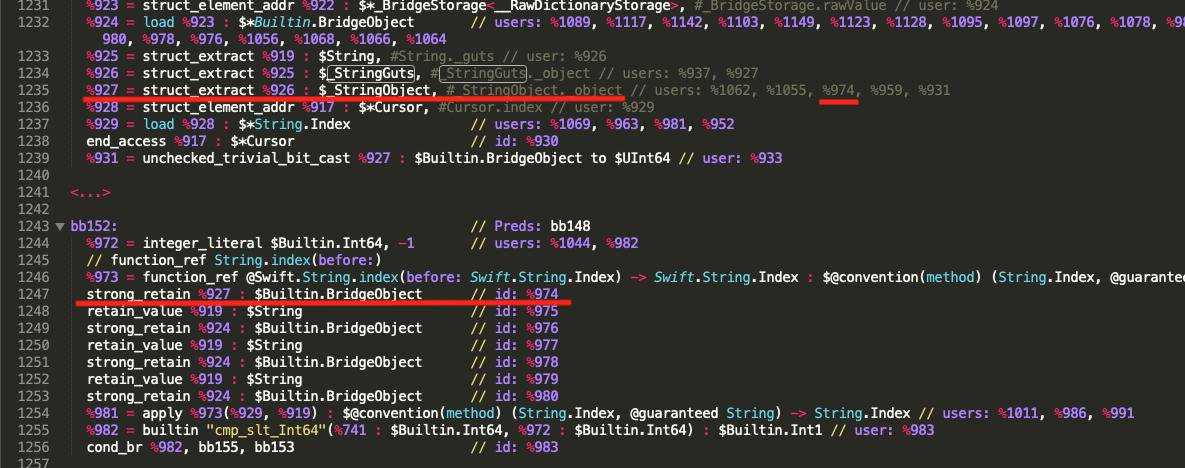

ARC #

ARC turned out to be one of the challenging parts to optimize. ARC has a huge impact on performance. And it is very hard to reason about. I had to drop to SIL level to make sure my changes have the desired effect. There is no easy way to do that from Xcode. I hope to make it a topic of one of the upcoming articles.

Fortunately, Swift team is working hard on optimizing ARC. There are even more optimizations to come in the future, like SIL ownership model, and potentially more control over memory management on the Swift code level. The current version of the compiler is quite generous in terms of how many retain and release calls it adds throughout your code. I can’t wait to see more improvements in that area.

The End #

That’s all! I hope you enjoyed this series. I’m pretty sure I got at least some of it wrong. If you have any corrections, please feel free to open a pull-request or drop a comment.

References

- Microsoft (2018), Backtracking in Regular Expressions, Regular Expression in .NET

- ICU, Regular Expressions

- OWASP (2017), Regular Expression Denial of Service

- Jan Goyvaerts (2003-2019), Regular-Expressions.info

- Regular Expression 101 (regex101.com)

- The IEEE and The Open Group (2004), The Open Group Base Specifications Issue 6 IEEE Std 1003.1, Part 9, Regular Expressions

-

To check whether the entire input string matches the regex you normally use Start of String and End of String anchors. ↩

-

Epsilon transitions don’t consume any input characters. We assume that the regex will never produce an NFA with loops which consist solely of epsilon transitions because that would lead to infinite recursion. ↩

-

Some regex engines also support possessive quantifiers which, like greedy quantifiers, consume as many characters as possible, but, unlike, greedy or lazy quantifiers, never backtrack. If the match fails, it fails. ↩

-

I’m using Python flavor which seems to use a backtracking algorithm similar to the one we implemented in the DFS section. Not every engine explicitly states in the documentation which algorithm it uses. But in general, you can deduce it by running a few experiments and testing running time and the shape of the matches that the engine produces. ↩

-

Apart from the tools like lazy and possessive quantifiers, almost every NFA language has some other fail-safe mechanism to deal with backtracking. For example, ICU (which

NSRegularExpression) sets the limit to the amount of heap usage. .NET Regex has a huge guide about how to optimize backtracking. They also offer tools like timeouts intervals and even disable backtracking completely. ↩ -

Not all regex engines are POSIX compliant, for example, .NET regex engine isn’t ↩

-

To prove that, try running the “evil” regex from the backtracking section of the article and select the flavor of regex without backtracking. If you are using regex101.com, that would be either ECMAScript or Golang flavors. They both return the result in a matter of milliseconds even on large inputs. ↩